1. Reading Prep

What you need to do to prep your readings for our asynchronous discussion.

To be completed within week 1, Sept 13 - Sept 19

The task

You have selected a suite of readings that are important or interesting to you. This week, you will set us up for a deeper engagement with the readings. You are the trailblazer, the guide, the scout, the point of first-contact, with a new and puzzling text. And boy, aren’t those all colonialist tropes. How else could we describe the action of someone whose job it is, is to read and guide our understanding?

You should provide a global ‘overview’ annotation, and around 3 - 5 good annotations on the document itself, to direct our attention to things that strike you as important.

Post in the ‘reading-prep’ channel in Discord which readings you have annotated; provide direct links.

The tool

You will use the hypothes.is web annotation tool to mark up the texts. Guidance for setting up an account for hypothesis, and using it to mark up pdfs and webpages, can be found here. You will need to join our hist5706 hypothesis reading group. When you have hypothesis turned on, and you’re logged in, you have the choice of posting your annotations to the ‘public’ group or our ‘hist5706’ group. Choose the latter; otherwise, anyone who has hypothes.is will be able to see your annotations.

Tips for annotating passages in the text

While the tips below assume you are writing your annoations, an annotation can also display video or audio. Optionally, you are welcome to use video or audio as well, if you’d like; this might work best for the page-level annotations (see below).

You can post video to youtube and mark it ‘unlisted’; then paste the URL to the video in the annotation. Hypothesis will automatically display the video in the annotation.

For audio, you might use something like soundcloud. Other options are available.

Look for what is puzzling, intriguing, or ambiguous in the text. If you read a passage, and you find yourself pausing because you’re not sure what you just read, that’s a good sign that here is something that needs unpacking.

Try not to annotate whole paragraphs. Keep the focus tight - a sentence or two; sometimes even just a phrase or a single word.

Use the toolbar within the Hypothesis annotation interface to emphasize your points. Use italics, bullet points, or bold text to highlight or emphasize as appropriate. Insert links to other relevant texts or annotations (every annotation has its own unique URL or ‘permalink’) if that will help to make your point. You can also insert images or youtube videos!

Add tags to your annotation to categorize the nature of the annotation or the idea under discussion. As we go through the course, we will see connections emerge between the readings as a result of these tags; when you write your case study, notebook, or exit ticket, being able to see all of the annotations using a particular tag (and then link to them) will deepen all our understanding of the materials.

Try to ask open ended questions, or make observations that invite more than ‘yes’ or ‘no’ responses.

Aim for at least 3 - 5 good annotations per paper.

Use Jon Udell’s Facet Viewer to keep track of annotations, so that you can respond in a timely fashion to other’s annotations. To use the facet viewer, you have to add your ‘API token’; this functions as a kind of key to uniquely identify your account. (You can find it here, when you’re already logged into Hypothesis). Once you copy your token, go back to the facet viewer page and scroll to the bottom. Paste it in the ‘Hypothesis API token’ box; then hit refresh on your browser. The facet viewer also gives you the ability to download annotations in a couple of different formats, by the way.

Tips for annotating the whole document (‘page’ annotations)

Your whole-page annotation gives a global overview of why this document is important, and what it offers to the rest of us.

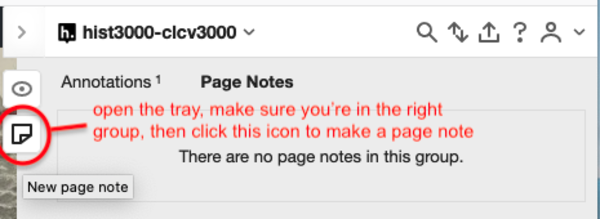

In this image, hypothesis is in the wrong group, so you’d hit the down arrow beside the group name to select the right group

You can make the annotation in text, or you can record yourself speaking about the document. If you choose the latter, you could make an ‘unlisted’ youtube video, and then paste the youtube URL into the annotation box. Hypothesis will embed the video directly. You could just record audio if you want; soundcloud.com can host those, and you could then just embed the link.

When appropriate, use the THOMAS mnemonic to help you create a succinct overview (by Danna Agmon). In some cases, only parts of the mnemonic will be useful.

THOMAS stands for ‘Topic Historiography Organization Method Argument So what’

You don’t have to address every aspect of the mnemonic in the same depth, and I’m not looking for essays here. But essentially, the mnemonic does cover all the bases for an effective summary that you are crafting for the benefit of your peers. Danna Agmon organized this mnemonic so that the questions are arranged in ascending order of importance, from least to most. So if you have to hedge your bets, the ‘so what’ is the most critical thing I want to see in your full-page annotation.

Topic: The basic questions: When? Where? What is this [item] about?

Historiography: What are the multiple scholarly conversations in which this work participates? What does it add to these conversations?

Organization: what is the central organizing structure of this work? Chronological? Thematic? Geographic? Are there any narrative devices put to use? How does the organization advance the argument?

Method: What sources are used in this book? How is this evidence analyzed? Is there an overarching theoretical or conceptual approach? How does the theory intersect with the evidence?

Argument: What is this author’s original thesis? What new thing does it explain?

So what? This could be rephrased as “significance” or “stakes.” What is important or useful about this [item], beyond the confines of the topic? Put differently, why would non-specialists in the field care to read this [work]?