Webmapping with Leaflet

Building a webmap using leaflet.js can be tricky.

Webmapping with Leaflet

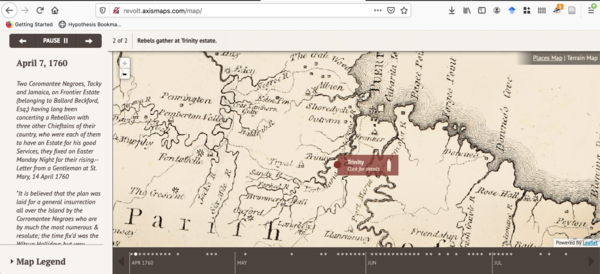

One of my favourite web maps is by Professor Vincent Brown of Harvard, on the Slave Revolt in Jamaica, 1760 - 1761. He writes, ‘the map suggests an argument about the strategies of the rebels and the tactics of counterinsurgency, about the importance of the landscape to the course of the uprising, and about the difficulty of representing such events cartographically with available sources.’ Spend a few minutes allowing the map to play (link here) and think about the aesthetic and design choices used to communicate this powerful story.

This map is made using the Leaflet.js open-source JavaScript library. Let’s start building.

For this next section, I am going to copy and modify an exercise from the Open Digital Archaeology Textbook Environment by Graham et al 2019; this particular section was contributed by Neha Gupta of UBC.

First of all, a webmap is not a Geographic Information System or GIS. A webmap may be derived from a GIS, but the key difference is that a GIS allows analytical questions to be asked of, and derived from, different layers of spatial or spatialized data. Webmaps are used more for conveying the results of such analyses.

Tiled map service and Web Map Service are two forms of Web-based mapping. A WMS is an interface that enables us (the clients) to request specific maps i.e. visual representations of geographic information from a geospatial database. The WMS server is called via a Universal Resource Link (URL) on an Internet-enabled desktop GIS. A request typically consists of the geographic layer (e.g. theme) and geographic area of interest. The response to a request results in geo-registered map images that are displayed and queried within a browser. Because the map is dynamically drawn upon request, and because the server typically uses the most current information from several layers in the geospatial database, WMS maps tend to load slowly.

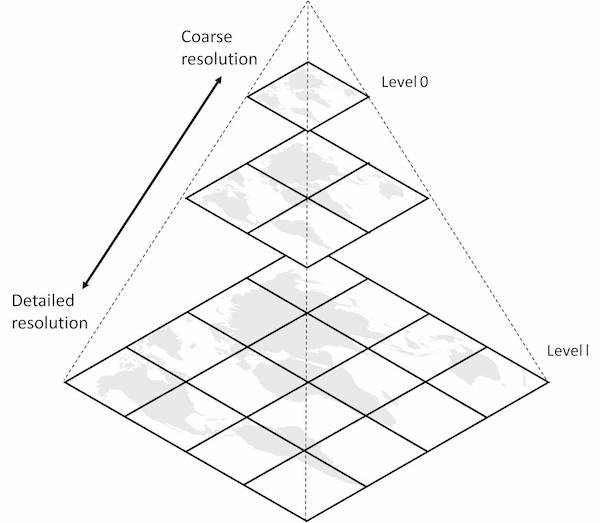

Tile map services such as TileMill Project, OpenStreetMap, and Stamen all use one or more vector layers that have been rasterized into an image. This rasterized image is divided into 256 x 256 adjacent pixel images or ‘tiles’. This is usually the base layer in a web map.

Each tile is an image on the Web, which means that you can link to it. For example, the following URL points to a specific tile on the Web:

https://tile.openstreetmap.org/7/63/42.png

The three elements in the URL are:

- tile.openstreetmap.org, the tile server name;

- 7, the zoom level or z value of the tile; and finally

- 63/42, the x and y values in the grid where the tile lives

The z value has a range between 0 and 21, where 21 returns a tile with greatest detail (and smallest sized tile).

‘Image Tile Pyramid, https://www.azavea.com/blog/2018/08/06/generating-pyramided-tiles-from-a-geotiff-using-geotrellis/tilepyramid/’

Once generated, the set of tiles are stored on disk, ready to be distributed rapidly to large numbers of simultaneous requests. Tiled maps load quickly precisely because they are pre-generated. They shift attention to map aesthetics and smooth map navigation, trading in functionality such as layer order, map scale and projection. Alex Urquhart maintains a list of tile services.

Data layers are typically added on top of the base layer. Data layers can be points, lines and polygons. These data layers are saved as GeoJSON, a format designed for representing on the Web, geographic features with their non-spatial attributes.

Leaflet is a JavaScript library developed by Vladimir Agafonkin for use with tiled maps. Launched in 2008, Leaflet has become widely used in tile web mapping because the library’s low-barrier customization and interactivity with map elements, and because of its simplified setup when compared to a WMS served map. Moreover, Leaflet’s compatibility with other Web 2.0 technologies and code-sharing platforms such as GitHub has encouraged an active community of ‘makers’.

- Create a new directory on your machine and call it ‘web-map’

- Open a terminal or command prompt in that directory.

- We’re going to build a map now; in sublime text make a new file and save it as

index.htmlin theweb-mapfolder. - We’ll begin by putting some important information about the building blocks we’ll use in the ‘header’ of our file, between the

<head>and<\head>tags. Copy and paste the following into your index.html:

<head>

<title>A Demo WebMap</title>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">

<link rel="stylesheet" href="https://unpkg.com/leaflet@1.6.0/dist/leaflet.css" />

<script src="https://unpkg.com/leaflet@1.6.0/dist/leaflet.js"></script>

<script src="https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1.11.1/jquery.min.js"></script>

<script type="text/javascript"></script>

</script>

</head>

This is telling the browser the name of this page, and it’s telling the browser where to get the stylesheet and the code for making the map work. You don’t have the leaflet.css or the leaflet.js files yet. Right-click, and ‘save as’ copies of these two files into your web-map folder from here: leaflet.css and leaflet.js

- The next bit of code defines the base map:

<body>

<div id="mapid" style="width: 600px; height: 400px;"></div>

<script type="text/javascript">

var myMap = L.map('mapid').setView([45.4192857, -75.6973237],13);

L.tileLayer('https://stamen-tiles-{s}.a.ssl.fastly.net/toner/{z}/{x}/{y}.png',

{maxZoom: 19

}).addTo(myMap);

We’re creating a box on the page called ‘mapid’ and setting its width and height in pixels. Then our script creates a thing called ‘mymap’ and defines some particulars about it: the center of the map (here, Ottawa, Ontario), the zoom level, and the basemap layer. The final bit, addTo(mymap); does the work of putting all of that information on the map (using leaflet.js).

- Now we’re going to need some data for our map. Our point data will be encoded in a format called ‘geojson’, which is a kind of list. If you have geographic data in a csv table, with latitude and longitude columns, you could use this tool to convert it to geojson. For now, our geojson has two points in it:

{

"type": "FeatureCollection",

"features": [

{

"type": "Feature",

"geometry": {

"type": "Point",

"coordinates": [-75.6973237, 45.4192857]

},

"properties": {

"Label":"Centre of our map!"

}

},

{

"type": "Feature",

"geometry": {

"type": "Point",

"coordinates": [ -75.699222, 45.4275 ]

},

"properties": {

"Label":"Not the centre of the map "

}

}

]

}

Copy that into a new file and save in your web-map folder as point-data.geojson

- Now append the following to the

index.html, which will tell leaflet where the data is and how to add it to our map:

// load a GeoJSON from external file

$.getJSON("point-data.geojson", function(data) {

// add GeoJSON layer to the map once the file is loaded

var datalayer = L.geoJson(data ,{

onEachFeature: function(feature, featureLayer) {

featureLayer.bindPopup(feature.properties.Label);

}

}).addTo(myMap);

});

</script>

</body>

</html>

Save!

- At the command prompt, you’ll use python to start a webserver; the webserver acts like a regular server and makes these two files understandable by your web-browser:

$ python -m http.server - The terminal will tell you now that your server is running at an address that will look something like this:

http://0.0.0.0:8000/orhttp://localhost:8000. Copy that full address and paste it into your browser’s address bar.

Congratulations! You have made a webmap! Do you see how you could recenter the map on Ottawa? Add some more data? Change the base map to another style?

(You can upload your web-map folder to Github by dragging the folder onto a repository; to make Github serve your website, you create a new branch called gh-pages. So if I loaded it into github.com/shawngraham/demo/webmap in the gh-pages branch, my map will be available at shawngraham.github.io/demo/webmap/index.html. Cool, eh?)

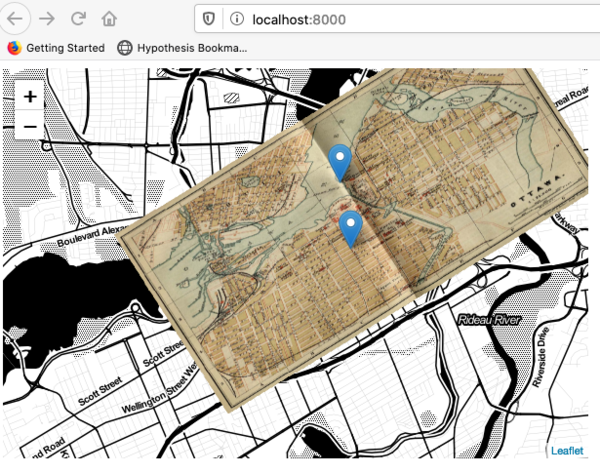

Adding a new layer to our map

Map Warper is a service that allows us to upload images of maps, and then tie ‘control points’ to real-world geography such that we stretch and warp the image to overlay the physical world. It then provides us with a tile-server so that the image can be imported into our map as its own layer. Take a look at this map of Ottawa:

.addTo(myMap);

Hit ‘enter’ a few times after that final semicolon, and then paste in this:

L.tileLayer('http://mapwarper.net/maps/tile/29435/{z}/{x}/{y}.png',

{maxZoom: 19}

).addTo(myMap);

Save the file, and then in your browser reload the page (I’m assuming you still have the server running as per step 8 in the previous section). Boom!

But that map is a bit wonky, compared to our base map. Let’s find a new map from Library and Archives Canada, georectify it, and then swap it in.

Georectifying a base map

But as historians, we are often interested to show some process taking place in the past, so historical maps can be rhetorically extremely useful as base maps. But, to get such a map into a digital format that we can use, we need to georectify it.

Georectifying is the process of taking an image (whether it is of a historical map, chart, airphoto, or whatever) and manipulating its geometry so that it matches a geographic projection. Think of it like this: you take your handdrawn map, and use pushpins to pin down known locations on your map to a globe. As you pin, your image stretches and warps. Traditionally, this has not been an easy thing to do, if you are new to GIS. In recent years, the curve has flattened significantly. In this exercise, we’ll grab an image, upload it to the Map Warper website, and then export it as a tileset which can be used in other mapping programs.

At Library and Archives Canada I found an “Insurance Plan of Ottawa, June 1878” MIKAN 3824226.

This one in particular shows Parliament Hill. I will save this one to my machine and georectify it. You grab one that interests you!

Go to Map Warper and sign up for an account. Then login.

Go to the upload screen:

Fill in as much of the metadata as you can - it’s important to credit the material correctly! Then select your map from your computer, and upload it.

On the next page, click ‘Rectify’.

Pan and zoom both maps until you’re sure you’re looking at the same area in both. Double click in a map, select the location icon, and click on a point (location) you are sure you can match in the other window.

Click on the other map window, select the location icon, and then click on the same point.

Note the ‘Add control point’ button below and between both maps will light up. Click on this to confirm that this is a control point you want. Do this at least three times; the more times you can do it, the better the map warp.

Having selected your control points, click on ‘Warp image’.

You can now click on the ‘Export’ panel, and get the URL for your georectified image in a few different formats. Copy the tiles based URL and put that URL into your

index.htmlfile as you did in the previous section.

Adding a layer control button

You can see that with leaflet it is pretty easy to add more layers and more data to your map. But soon things get a little bit unwieldy. We’re going to re-organize our map so that we can turn layers on and off.

The end result will look like this:

We’re going to create some variables to hold our different layers and maps. Make a copy of your index.html file and call it index2.html. Open index2.html in Sublime Text and work on that file.

- Delete the code from the

var myMap =line to the// load a GeoJSON from external file. Your code should look like this now:

<body>

<div id="mapid" style="width: 600px; height: 400px;"></div>

<script>

// load a GeoJSON from external file

We are going to create four variables that contain the different layers we want to show. Two are going to be base maps from Stamen (the ‘toner’ map and the ‘watercolor’ map), and two are going to be georectified maps we found on MapWarper showing downtown Ottawa. Insert after the <script> tag:

var toner = L.tileLayer('https://stamen-tiles-{s}.a.ssl.fastly.net/toner/{z}/{x}/{y}.png'),

watercolor = L.tileLayer('https://stamen-tiles-{s}.a.ssl.fastly.net/watercolor/{z}/{x}/{y}.png'),

historical1897 = L.tileLayer('https://mapwarper.net/maps/tile/29435/{z}/{x}/{y}.png'),

lumberdistrict = L.tileLayer('https://mapwarper.net/maps/tile/27671/{z}/{x}/{y}.png')

The L.tileLayer tells leaflet the sources for our layers.

Now we’re going to create two more variables to group our layers into base maps and overlay maps:

var baseMaps = {

"Toner": toner,

"Watercolor": watercolor

};

var overlayMaps = {

"1897": historical1897,

"Lumber District": lumberdistrict

}

Next, we create a variable called myMap to tell Leaflet the centre of our map, the zoom layer, and the default base map; we pass this information to the html container ‘mapid’ so that our creation can be displayed:

var myMap = L.map('mapid', {

center: [45.4192857, -75.6973237],

zoom: 13,

layers:[toner]

});

and finally, we add a control box so that we can switch the different layers on and off, and that our layers are grouped appropriately:

L.control.layers(baseMaps, overlayMaps).addTo(myMap);

Save that as index2.html, and with your server still running, you can view it in your browser at http://localhost:8000/index2.html. (NB: the part after the colon might be different on your machine - this number is the ‘port’ and the precise port number will have printed out in your terminal when you first ran the python -m http.server command.)

For more on layers with leaflet, see Layer Groups and Layers Control.

Adding animation

Animating points in your map, so that they move along a path, is relatively easy to accomplish. We’ll use the Animated Marker plugin.

Go to that repository, and click on the

srcfolder, then theAnimatedMaker.jsfile. This is the code that actually does the animation. We need to make this code available to our map. If you click on therawbutton, you’ll get a page with just the code that you can copy and paste into a new document in Sublime Text. Save this file asLeaflet.AnimatedMarker.jsin yourweb-mapfolder.Now, make a copy of your

index2.htmland change its name toindex3.html. Openindex3.htmlin Sublime Text.In the code between

<head>and</head>in our index3.html file we specified the location of the javascript we’re using to make our maps. We have to add the animated marker javascript file here as well. Add:

<script src="Leaflet.AnimatedMarker.js"></script>

so that that part of your code looks like this:

<script src="https://unpkg.com/leaflet@1.6.0/dist/leaflet.js"></script>

<script src="https://ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1.11.1/jquery.min.js"></script>

<script src="Leaflet.AnimatedMarker.js"></script>

<script type="text/javascript"></script>

You can add scripts located elsewhere on the web, or from within the same folder as your index.html.

- We’re now going to define a path for our marker to move along, and we’ll give it three points to move along:

var line = L.polyline([[45.4245941,-75.6953823],[45.423299,-75.6927912],[45.4174419,-75.6907598]]),

animatedMarker = L.animatedMarker(line.getLatLngs());

You could add more points by adding latitude and longitude pairs in decimal degrees, where each pair is wrapped in [ ] and set off from the other pairs with commas. Insert that code after the L.control.layers line.

- And then, add that animated path as a layer to your map with this line:

myMap.addLayer(animatedMarker);

Save that file, and open it in your browser. Watch that third marker move!

To extend Leaflet with more capabilities, consult this list of plugins and associated documentation.