Text Analysis: Voyant

Voyant has been called the gateway drug for the digital humanities.

Text Analysis in a Nutshell

…so let’s take a look at Voyant Tools:

An Introduction to Voyant

“The gateway drug to the digital humanities.” That’s quite a statement - but it’s true! What makes Voyant Tools so compelling, in my view, is that it encourages us to play. To take a step back, and turn the knobs and dials and to see what happens next. Voyant encourages us to zoom in and out, looking at the very broad macroscopic and then jump into the micro, and back again. Each tool panel in Voyant can be embedded into a new document, so that you can share what you find, or so that you can write an argument and your readers can explore your data at the same time.

So let’s do that. Dr. Melodee Beels of Loughborough University in the UK has been studying the ways early newspapers reprinted articles from their competitors (Here is a presentation she gave on her research from a few years ago). In the course of this work, she has put together a database of these articles. One ancillary question that Dr. Beels is interested in are the ways British newspapers framed Britain’s relationship with its colonies.

A subset of her data is available here where each row is a unique article, and each column is field describing some of the metadata for that article. Can you determine anything about what broad patterns are in them? Not really, eh? Not without reading and making notes on every single row. So let’s take a distant read instead.

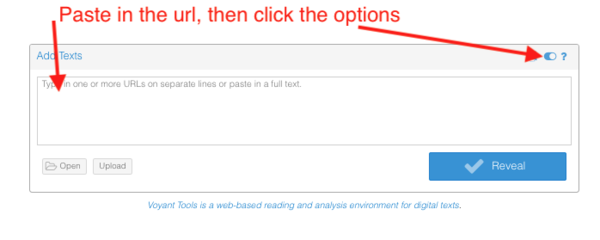

- Now, Voyant can read one row at a time in a table, and consider it a unique document - if the table is in Microsoft Excel format. I converted that csv to xlsx and I’ve made it available for you here. Right-click on that link, and ‘copy link location’. At Voyant Tools paste that link in the ‘Add Texts’ box but don’t hit ‘Reveal’ yet.

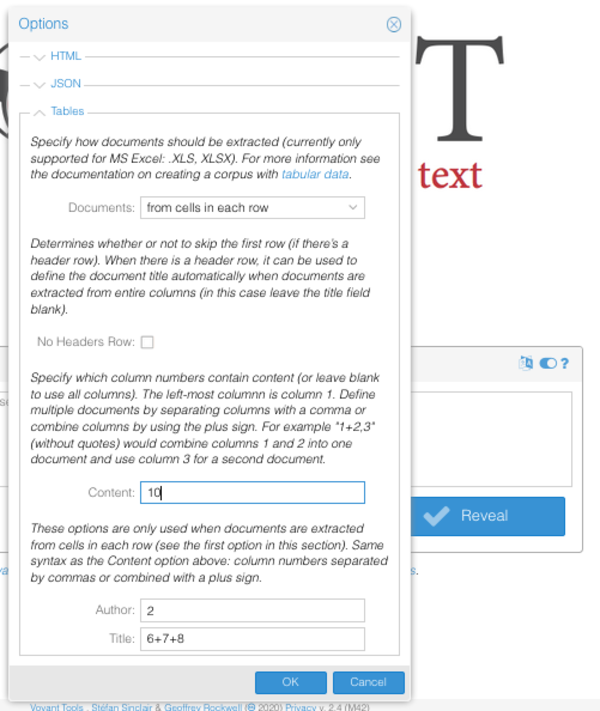

- Click on the options button at the top right. We have to tell Voyant how to parse our table. We are going to tell it that we are uploading a table by making changes under the ‘tables’ option. The newspaper articles themselves are in the 10th column of our spreadsheet, while the author metadata is in the 2nd column (the name of the newspaper) and the ‘title’ we’ll create by combining the date columns (which are the 6th, 7th, and 8th columns). Thus, enter

10in content,2in author, and6+7+8for title. This way, Voyant will read each row as a separate document, with useful metadata.

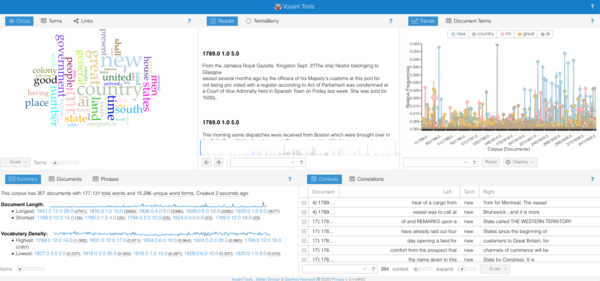

- Hit ‘ok’ and then hit ‘reveal’. You should see something rather like this:

- Make a note of your corpus id; you’ll find it in the URL, after the

?corpus=. Here’s the URL for the version I made:https://voyant-tools.org/?corpus=ea1868d7f1fbece8f0f5538c23a3128e. You can return to your corpus or share your corpus with someone else by giving them that URL. As you explore Voyant, note how the URL changes to reflect the name of the tool, and the settings you applied. You’ll notice too that if you mouse over the title bar for the different sections, an export option will appear, everything from a url to the html to embed the whole tool and data in a website.

Explore the Newspaper Corpus

Before you explore, make a note of some of the questions you might like to ask, knowing what you know about how this corpus was put together, and what you think you might know about how Britain regarded its colonies in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Normally, you would frame your questions and your hypotheses about the data before you started to collect it, because these hypotheses help you understand what evidence you’d need to gather, and would help you understand when to stop gathering the data. Obviously, we are constrained here because we are using someone else’s corpus: but maybe you can still see some questions worth asking? Reusing primary research is not something that we are comfortable doing, in History; we much prefer to redo the original research each time because we are all Heroic Lone Scholars. But that’s not really a good use of everyone’s time and energy. There are times when reusing someone’s corpus or data or workflow can be used to generate new insights, or confirm existing ones; this is something historians have to get used to doing.

Rockwell and Sinclair recommend ‘entering into a dialogue with a text’. They write,

One way to think about how you can study a text is to think about entering into a conversation with the text through Voyant. Think about questions you might ask about the text like:

- What is this about? What words would I expect to see as describing the text?

- What does this text say about something that matters to me like “friendship”?

- What words in the Cirrus word cloud make sense, and what words are anomalous?

- How does the language of the text change over the span of the text? Are some words more important in the beginning and some at the end? Could there be framing words? Text analysis tools like Voyant grew out a tradition of developing concordances for important texts like the bible or Shakespeare’s plays. Concordances were printed tools like indexes that allowed a preacher or scholar look up a word like “friendship” and see all the instances across the bible in one place. She could then think through friendship and prepare a sermon or paper discussing the theme. With Voyant you can now study any electronic text in a similar fashion. Try it!

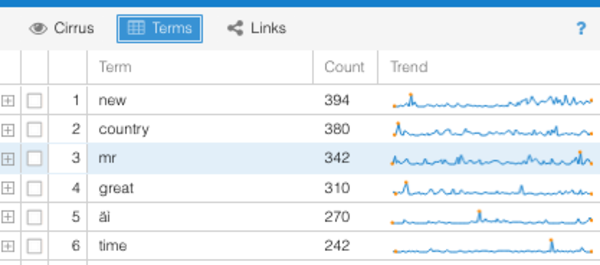

Try identifying themes in the materials you’re looking at. Beside the word ‘cirrus’ (eg, Voyant’s wordcloud tool) there is the word ‘Terms’. If you click that, you’ll see the same information but this time represented as a table with counts of the number of times the word appears in the corpus, and a small ‘spark line’ graph showing roughly where the term is most prominent (since our corpus is organize in chronological order, the left side of the spark line is the oldest material, and the right side is the newest).

Does anything jump out at you? Click on the term. What changes in Voyant?

In the ‘trends’ box, click on one of the high points; the ‘Contexts’ panel will change to show you ‘key words in context’ for that term, or five words to the left, and five words to the right, which enable you to start doing a close reading of the particular document.

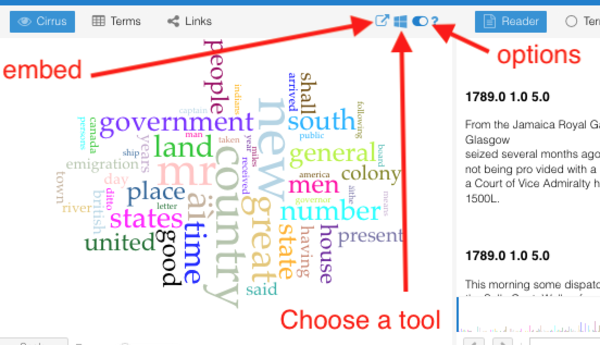

Thus Voyant Tools enables you to cycle from distant to close reading and back again! Play with some of the customizations or other tools, and see if you can find any interesting patterns. Export anything interesting you find by hitting the button I labelled ‘embed’ in the image below (‘export’), and then selecting ‘HTML Snippet’. This snippet can be saved in a markdown file and uploaded to Github; if your repo is set up to feed a static website Github will render your widget as html!

A dialog box will appear, and give you some html like this to save into your file:

<iframe style='width: 530px; height: 315px;' src='https://voyant-tools.org/tool/CorpusTerms/?corpus=ea1868d7f1fbece8f0f5538c23a3128e'></iframe>

Note how the URL contains the name of the tool, and the path to your corpus. When this is displayed as html, it will look like this, a fully interactive widget! (Move your mouse over this; you can start exploring things.)

If you double-click on anything in that widget, a new window will open bringing you to the full version of my corpus.

Voyant is an excellent tool because it embraces the reader in the process of making meaning from the data. In many ways, it was a natural extension of the way its creator approached everything he did.

Add words to the stop list

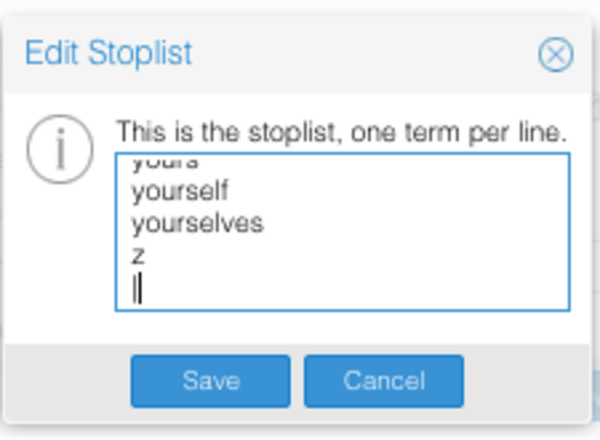

You can add words to the ‘stoplist’ tp tell Voyant to filter those words out - typically, you’ll see in the wordcloud some words that shouldn’t be considered, given the context of your materials - ‘newspaper’ maybe, in this example. To add words to the stoplist,

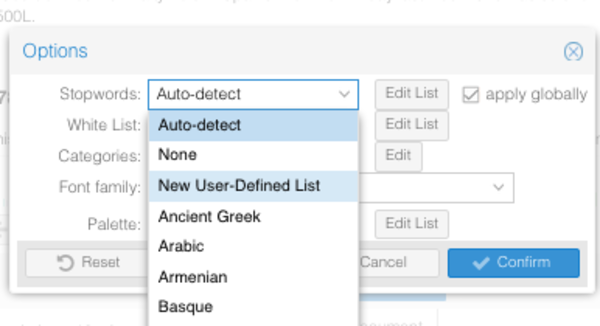

- Select the ‘options’ button in the word cloud panel.

- Select ‘English’, and then ‘Edit List’. You can add words, one line per word, and then ‘confirm’.

Going a Bit Further: Build Your Own Corpus

- Search the Chronicling America database for articles of interest; say you’re interested in how Canada has been represented to the everyday reader of newspapers in the US. Use what you learned in part two to assemble the data (eg, you’ll need to be familiar with the APIs tutorial).

- Arrange each article in a spreasheet (use Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets), such that you have the following:

| date | headline | article-text |

|---|---|---|

| 1964 | Man Bites Dog | Anytown, USA. A man bit a dog yesterday… |

| more | rows | of data |

Save it as .xlsx. Import it into Voyant. Share your corpus with your classmates. Do some initial explorations - does anything jump out at you?

Going A Lot Further

Voyant Tools lives on a server in Montreal. When we use its web interface, we are transmitting data back and forth from our machine to the machine in Montreal. There’s no necessary guarantee that anything we share couldn’t be intercepted somehow. If you are working with sensitive materials - oral history transcripts, say - you ought not to be using a web-based tool to analyze them. There is also the issue of storage. Materials that are uploaded to Voyant Tools can and do get deleted eventually if they are not regularly accessed.

The solution is to download and run Voyant Tools yourself! Just as you did with Open Refine, you can have Voyant run in a virtual server on your own machine, and you can then interact with it through your browser as if you were using the main Voyant Tools. The instructions for downloading and installing Voyant Tools on your own machine are here. Give it a shot! With Voyant Tools on your own machine, you do not need to worry about sensative materials finding their way onto the web.